Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

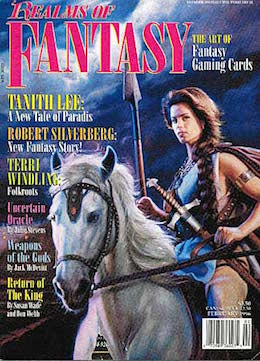

Today we’re looking at Robert Silverberg’s “Diana of the Hundred Breasts,” first published in the February 1996 issue of Realms of Fantasy. Spoilers ahead.

“And for a moment—just a moment—I seemed to hear a strange music, an eerie high-pitched wailing sound like the keening of elevator cables far, far away.”

Summary

Tim Walker’s on his annual tour of Mediterranean ruins. He can afford to prowl the world without profession because, like older brother Charlie, he’s lucked into a seven-figure trust fund. Charlie’s also a genius with movie-star good looks, winner of trophies and prom queens, now a renowned professor of archaeology leading a dig at Ephesus. Tim’s always felt like “Charlie-minus, an inadequate simulacrum of the genuine article.” But Charlie’s charm has a razor-edge of cruelty; if Tim took him seriously, he’d probably hate his brother. Tim doesn’t take much seriously. Neither does Charlie. Tim thinks.

Tim and Charlie meet Reverend Gladstone. Charlie suggests Gladstone visit the house where the Virgin Mary lived—as he doubtless knows, Ephesus was always a center of mother-goddess worship. And Gladstone better come to the Seljuk Museum to see the statues of Diana of the Hundred Breasts, the “celestial cow that nourishes the world.” Seeing her will be his best way “to understand the bipolar sexual nature of the divine.”

Though aware of Charlie’s facetiousness, Gladstone accepts the invitation. The next day finds the three in front of the larger Diana, a nine-foot tall woman wearing a huge crown and a cylindrical gown carved with bees and cattle. Her midsection is “a grotesque triple ring of bulging pendulous breasts.” Though maybe they’re eggs, says Charlie, or apples or pears. Globular fertility symbols, for certain. He, himself, thinks they’re tits. An abomination before the Lord, murmurs Gladstone, which should be smashed and buried. Charlie pretends piety: that would be a crime against art. Gladstone refuses, good-naturedly, to argue with a cynic and sophist.

To Tim, he remarks that he pities Charlie. Poor empty-souled man, he seems to think all religions are silly cults. Not quite, Tim says. Charlie thinks they’re all fictions devised by the priests and their bosses to control the masses. See, Charlie lives and dies by rational explanations. Ah, says Gladstone, quoting St. Paul’s definition of faith, so Charlie’s incapable of giving credence “to the evidence of things not seen.”

That night Charlie calls Tim to his excavation site. Through sonar scanning, he’s found an uncharted tunnel branch, and a funeral chamber behind a circular marble slab. Defying proper procedure, Charlie’s eager to have first look inside, with Tim the only accomplice he can trust. They break clay seals inscribed with characters in an unknown language. As they lever out the marble slab, “ancient musty air” roars out of the black hole revealed. Charlie gasps. Tim feels a jolt. His head spins, and he hears strange music, “an eerie high-pitched wailing sound like the keening of elevator cables.” He imagines “that I was standing at the rim…of the oldest well of all, the well from which all creation flows, with strange shadowy things churning and throbbing down below.”

The weirdness passes seconds later, and Charlie angrily denies their shared experience. It was just bad air. And look, the tomb of treasures is just an empty chamber five feet deep!

The next night Charlie drags Tim out again. Now, he admits, there’s no use denying they let something out of the tomb. Reliable people at the site have seen her—seen Diana of Ephesus, walking the ruins since sundown.

When they reach the site, “Diana” has headed into town. Charlie and Tim pursue something with a very tall conical body, weird appendages, and a crackling blue-white aura—it seems to float rather than walk. In its wake, the residents of Seljuk are either prostrate in prayer or fleeing in terror. It continues on its “serene, silent way” toward the hill looming over the town, the acropolis of the Byzantines.

The brothers follow it to the ruined basilica on the hilltop. Tim hears again the eerie music. It seems to reach to distant space, a summons. He sees that Diana’s eyes are insect-faceted, that she has extra arms at the hips, that despite her “breasts” she’s more reptilian than mammalian. Her skin’s leathery and scaly, her tongue black and lightning-bolt jagged, flickering between slitted lips as if testing the air. He wants to drop and worship her. Or run like hell.

Charlie, on the other hand, confronts this creature that dwarfs him, that surrounds itself with a cocoon of dazzling electricity. What the hell are you, he demands, an alien from another planet, another dimension? A member of a prehuman race? Or a real goddess? If a goddess, do a miracle!

The creature makes no response.

Charlie tries speaking to it in ancient Greek. No response. He goads it by calling it a fake, a hallucination. No response. Furious, he charges at it, half-roaring, half-sobbing “Damn you!”

The creature’s aura flares. Cold flame whirls through the air stabbing Tim’s brain, felling him. He sees the energy coalesce into one searing point of white light that streaks comet-like skyward and vanishes. Then he blacks out.

He and Charlie regain consciousness at dawn. Charlie questions whether anything happened at all, but Tim knows what it must be doing to him, to have witnessed so fantastic an event and have no explanation. They return to Tim’s hotel, where Gladstone sees something’s shaken them both—how can he help? They tell him their whole story, which he takes seriously. Perhaps it was Solomon’s seal on the tomb they opened, for Solomon imprisoned many evil djinn.

Charlie tries to scoff. Gladstone’s not buying. He says Charlie’s been undone by the evidence of things seen. Charlie corrects his quote of St. Paul—it’s the evidence of things unseen. Not in Charlie’s case, Gladstone insists, because this time Charlie saw. The man so proud of believing in nothing can no longer believe even in his own disbelief.

Charlie chokes on a retort, then stalks off. As he leaves, Tim sees the look in his eyes. Oh, those frightened, empty eyes.

What’s Cyclopean: Diana’s breasts are “grotesque” and “pendulous.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Charlie makes a variety of mildly misogynistic comments about Diana. Tim makes a variety of mildly objectifying comments about the women among his fellow tourists. He also makes an extremely gratuitous joke about committing “abominations before the lord” with Gladstone.

Mythos Making: Diana has a vaguely Nyarlathotepian look about her, but it seems unlikely that It has been locked up behind a Solomon’s Seal all this time. Charlie is really the most Mythosian thing about this story.

Libronomicon: Mr. Gladstone’s late wife wrote a children’s book about the Seven Sleepers

Madness Takes Its Toll: Charlie does not react well to the inexplicable—or even the not-likely-to-be-explained.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I spent the first part of “Diana of the Hundred Breasts” wondering if this story was just going to annoy me by conflating Mythos-worship and classical Paganism—or worse, by conflating Mythos-worship with the terror of feminine power. But no, it legitimately earns its Lovecraftian label. Just not in the way I expected. Sure, the thing behind the seal is strange of form and great in power. But Charlie’s the one who insists on making the whole thing cosmically horrible.

One of the patterns we discovered in reading Lovecraft’s original oeuvre is that often, the point is not the reveal of the scary thing to the reader. It’s the narrator (or the narrator’s intense-yet-problematic friend, or the guy who wrote the journal the narrator’s reading) coming slowly to acknowledge the scary thing, and more importantly the way the scary thing overthrows their formerly stable worldview. For Lovecraft, civilization is bulwarked by tissue-thin lies, easy to pierce. That breakdown, in an individual or a whole society, becomes the source of true horror.

One aspect of civilization that Lovecraft was less than fond of was religion. “Bunch together a group of people deliberately chosen for strong religious feelings, and you have a practical guarantee of dark morbidities expressed in crime, perversion, and insanity.” Just a sample, and in case you thought the New Atheists invented this stuff. So Charlie is right up Lovecraft’s alley. A fundamentalist atheist—not truly a scientist willing to live with doubt, but someone attached to specific certainties—he’s perfectly suited to have his bulwark beliefs overturned by Diana. Whatever she is. For a true scientist, she’d be the source of a cornucopia of new hypotheses, competing theories, lines of research to outstrip a lifetime. For Charlie, she rips open the “hollow place” where he isn’t truly open to the evidence of his own experience. Mr. Gladstone isn’t wrong. (About that, at least. Still not forgiving him for wanting to destroy the historically-important statues.)

Perhaps a better Lovecraft quote on religion would have been: “If religion were true, its followers would not try to bludgeon their young into an artificial conformity, but would merely insist on their unbending quest for truth…” Charlie is intended, I suspect, to show that Lovecraft’s test holds for any belief too rigidly held. The cost of that rigidity, for him, is a classic Lovecraftian character arc. Once the unknown rears its head (appendages, pyramidal torso, etc.), he can’t stay away. He races after it, has to track it down and confront it face to face, even—or perhaps because—knowing the likely cost of that meeting. For Charlie that confrontation has to be a direct one. He’s fortunate that his particular unknown reacts well to being shouted at by apoplectic mortals.

I do keep coming back to that “whatever she is,” though. The connection to Diana of the Hundred Breasts herself is, in fact, pretty tenuous. A pyramidal alien interred in close proximity to a temple is not necessarily the entity originally worshipped at that temple. She does have the vaguely-mistakable-for-breasts, though. And worship of some sort does seem likely, given that she projects the desire to grovel every time Tim gets close. She doesn’t seem too attached to continued worship, though, heading Elsewhere as soon as she can catch a ride. So maybe eliciting worship from mortals is just a survival strategy—an ecological niche ripe to be filled. And to be studied by xenobiologists, since Charlie has so little interest in going for a share of that grant money.

As with so many Lovecraftian stories, pick another protagonist, and there’d be no horror. There might be science fiction instead, or thoughtful metaphysical speculation. Genre, like so many other things, is all about how you react.

Anne’s Commentary

Back in the days of my misspent youthishness, I wrote a Star Trek Next Generation fanfic in which Moriarty trapped Picard in a virtual reality indistinguishable from “real” reality. You know, your typical lousy Monday in the ST universe. Bad things were happening on the Enterprise. I mean, major-character-DEATH bad things. Or were they happening? Moriarty tormented Picard by continually reminding him that no matter how firmly Picard believed the bad things were a simulation, unreal, he didn’t know it.

Surely Picard was no man of faith, content to hope for the insubstantial, to accept as evidence the things unseen? No, he had to be a man of science, of fact, of only things seen and otherwise sensed! Or, clever fellow that he was, could he perform such feats of mental agility as the juggling of faith and reason?

Absolutely Picard couldn’t be one of the contemptible sort strung together of quivering nerves, believing what he wanted to believe, seeing what he wanted to see.

I forget whether Picard punched Moriarty at this point, or whether they just had some more Earl Grey and crumpets. I do know that in our survey of revelations sought and found, we’ve seen both mystical/religious and scientific approaches, with some wishful believing snuck in at the stress lines of faith and rationality.

Now, if Moriarty wants a pure rationalist at his table, he could invite Silverberg’s Charlie Walker. Ask bro Tim: Charlie’s a SCIENTIST, “a man who lives or dies by rational explanations. If it can’t be explained, then it probably isn’t real.” And so dedicated is Charlie to the real that he has only contempt for religion and revels in challenging Gladstone’s faith. His intellectual certainty overflows with such lava-hot joy that it scalds others; yes, Charlie is brilliant but cruel.

Still, if Charlie’s unshakable in his allegiance to Reason, why does Gladstone feel so strongly that he’s missing something, that he needs help? Does Gladstone see something Tim doesn’t, or does the minister retaliate against Charlie’s attacks on his Christianity through some wishful thinking of his own? We get hints in the very persistence of Charlie’s assaults—the rationalist does scoff too much, methinks. Also in his feverish eagerness to open the sealed tomb chamber alone. Followed by the over-vehemence of his protests that he felt nothing strange when the marble slab yielded.

Oh, Charlie, you cool boy. Could it be you’re looking for something more than even you already have? Looking with such raw need that you’re desperate to hide it? Wouldn’t it be killing if this insignificant little man from some midwestern state starting with “I” saw through you?

Wouldn’t it be even more killing to meet a creature who was the inspiration for a human mother goddess, many-teated (to your eye, at least), all nurturing? Then to have that creature ignore you? To refuse to explain itself, to classify itself for you, Charlie the scientist? To refuse, a god by its relative powers, even to accept your implied bargain for worship by performing a miracle? To refuse you, finally, the right to prove it real by striking it, touching it?

It might have been a comfort to have the defense of denial, but Charlie saw the creature, and so did Tim, and so did dozens of others in the town and at the dig site. As Gladstone tells Charlie, he’s been undone by the evidence of things seen, and the pride he took in believing in nothing has been shattered.

A mystery has found Charlie. He keeps trying to name it: goddess, supernatural being, alien, djinn. Gladstone’s seemingly offhand “Does it really matter which it was?” is actually a critical question. Charlie fears not knowing; fear’s the first half of our classic emotional dynamic. Can he pass through that to the second half, awe, in which the experience suffices?

If he can get to awe, to wonder, I think he’ll start filling the emptiness Tim mourns seeing in his brother’s eyes.

Next week a bit of Lovecraftian juvenilia, and a cave with something in it, in “The Beast in the Cave.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.